Blog

Wielding Empathy

Empathy is often described as one of the noblest of human capacities. It is the ability to place oneself in another’s situation, to feel—at least in part—what they feel, and to respond with compassion and understanding. In our age of rapid communication and constant noise, empathy stands out as a rare and transformative skill. But here’s the truth: though many people toss the term around as a buzzword, real empathy is not so simple, nor is it something that can be cultivated overnight. To wield empathy effectively, we must go deeper than platitudes and surface-level sympathy.

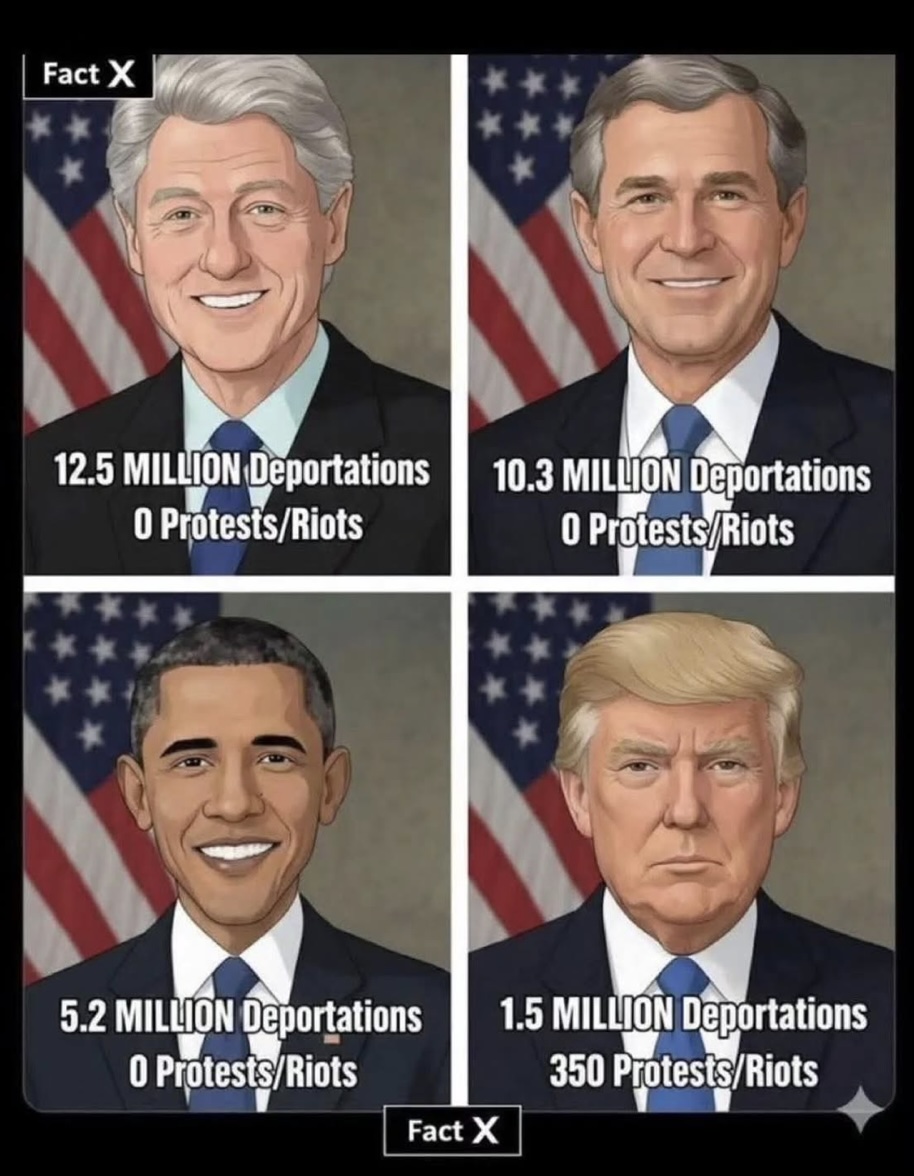

Empathy: More Than a Word

Empathy has become a staple in self-help seminars, corporate mission statements, and social media captions. You’ll hear leaders proclaiming the need for “empathy in the workplace,” and individuals describing themselves as “empaths” as if it were a personality badge. While this widespread attention is not inherently bad, it can blur the meaning of the word itself.

True empathy is not about casually nodding when someone speaks or saying “I understand” without listening. Nor is it about projecting our own feelings onto another person and assuming their experience is identical to ours. Empathy is, instead, the disciplined art of seeking to understand the inner world of another—emotionally, mentally, and even spiritually—while setting aside the urge to judge or immediately fix.

As Stephen R. Covey wrote in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, “Most people do not listen with the intent to understand; they listen with the intent to reply.” Covey highlighted what he called empathetic listening—listening not just with the ears, but with the heart. This is not passive but highly active work: it requires concentration, patience, humility, and the suspension of our own filters long enough to genuinely absorb another’s perspective.

The Limits of Empathy

Still, it would be misleading to present empathy as limitless. The fact is, no matter how much we care, we can never fully step into another person’s shoes if we ourselves have not “been there.” To empathize with a grieving parent, a combat veteran, or a refugee fleeing their homeland requires imagination and openness—but imagination is not lived experience. What we achieve at best is an approximation.

This does not make empathy any less valuable. In fact, it makes it even more vital. When we acknowledge that our grasp of another’s feelings is inherently incomplete, we approach them with humility. We resist the temptation to say, “I know exactly how you feel,” and instead say, “I can’t fully know your experience, but I want to understand as much as I can.” That honesty can open the door to trust more effectively than pretending total understanding.

Empathy Is Not…

To sharpen the distinction, it helps to clarify what empathy is not:

• Empathy is not sympathy. Sympathy acknowledges another’s struggle from a distance—“I feel bad for you.” Empathy closes the gap—“I feel with you.”

• Empathy is not agreement. You can empathize with someone’s feelings without agreeing with their choices or worldview. In other words, when it comes to empathy, you may or may not agree with the other person — the question of agreement lies outside the purview of empathy.

• Empathy is not indulgence. It does not mean validating harmful behavior; rather, it means understanding the why behind behavior.

• Empathy is not projection. Assuming another person feels as you would in their situation isn’t empathy; it’s self-centered guessing.

How to Develop the Skill of Empathy

If empathy is more than a buzzword, then how do we actually cultivate it? Here are some practices to consider:

1. Practice deep listening. Resist the reflex to formulate your response while someone is speaking. Listen with the intent to understand, not to reply. As Covey emphasized, truly hearing another person may require reflecting back what you’ve heard: “It sounds like you’re feeling overwhelmed because…”

2. Ask clarifying questions. Rather than assuming you know what someone means, ask: “Can you tell me more about that?” This not only deepens your understanding but also communicates genuine interest.

3. Suspend judgment. Judging interrupts empathy. When you label someone’s feelings as irrational or wrong, you cease to inhabit their perspective. Focus first on seeing their reality before analyzing it.

4. Expose yourself to diverse perspectives. Literature, film, and conversation with people outside your own circle expand your emotional vocabulary. They give you reference points for experiences you may never live yourself.

5. Be present. Empathy can’t be rushed. Often, what people need most is simply your undivided presence. The act of sitting with someone in their pain or joy, without trying to escape or fix, is one of the purest forms of empathy.

6. Recognize your own limits. As mentioned earlier, empathy is incomplete if we haven’t walked the same road. Acknowledging this limitation allows us to stay authentic and prevents the hollow comfort of clichés.

7. Practice Naive Listening. Naive listening complements deep listening by stripping away the assumptions and baggage we bring into conversations. It is the discipline of listening as if you were an innocent vessel—uncluttered, unburdened, and curious. Imagine a child hearing something for the very first time: they don’t jump ahead, they don’t predict, they simply receive. Practicing naive listening means banishing the thought, “I already know where this is going.” Even if you are convinced you’ve heard it before, you stay open to the possibility that you may be wrong—or that this time, it will carry a nuance you’ve missed before. Naive listening allows people to feel freshly heard, not squeezed into a box of your past understandings.

The Power of Wielding Empathy

When wielded skillfully, empathy can transform relationships, organizations, and even communities. Leaders who practice empathetic listening cultivate loyalty and trust. Friends who embody empathy provide safe harbors for one another in times of storm. Couples who empathize dissolve conflicts before they escalate.

Yet empathy must be more than sentiment. It becomes powerful when it translates into thoughtful action. To sit with someone in their pain is empathy; to help alleviate that pain when possible is empathy in motion.

Conclusion

Wielding empathy is not easy work. It demands humility, patience, and a willingness to step outside of ourselves. It asks us to acknowledge both the reach and the limits of our understanding. It reminds us that while we may never fully grasp what another has endured, our efforts to listen, connect, and care can make a profound difference.

As Covey noted, when we truly listen with empathy, we give people “psychological air.” We help them feel seen, heard, and validated—and in a world that often leaves people gasping for such air, that is nothing short of life-giving.

To wield empathy is to wield one of the most transformative tools of self-development and human connection. It is not a buzzword. It is not a trend. It is, at its heart, a practice—a noble one, and one well worth pursuing.